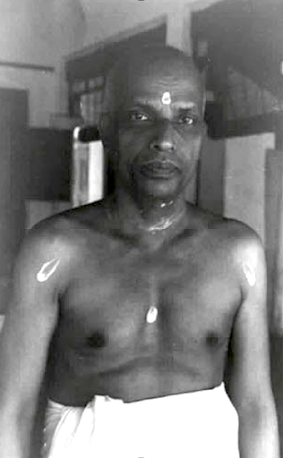

Shri Atmananda (Krishna Menon)

– one of the greatest teachers of the twentieth century

by Philip Renard

It is a pity that until this day the great Advaita teacher Shri Atmananda (Shri Krishna Menon, called Gurunathan by his disciples) remains a rather unknown figure to many people. With this article I hope to contribute to the recognition of the importance of him as a Source for direct understanding of ultimate Truth.

Two small books written by him, Atma-Darshan and Atma-Nirvriti, form together in fact a modern Upanishad. Upanishads are classical texts that have been added to the Vedas as concluding parts since about the eighth century BC. The term Vedānta (Veda-anta) indicates this; it means ‘the end (anta) of the Vedas’, and is a reference to the Upanishads.1 A modern Upanishad is a collection of statements so definite that the Vedanta tradition begins again, as it were. Not a commentary on something existing, but a text that has emerged from current, ‘ever fresh’ Consciousness.

Shri Atmananda was born P. Krishna Menon on December 8, 1883, in Peringara, near Tiruvalla, in Travancore (in the present-day Indian state of Kerala). He passed away on May 14, 1959 in Trivandrum, the capital of Kerala. In the course of his life he has been a true Teacher (a so-called Karana Guru) for many people, including a number of westerners. It is true that some western intellectuals who approached him were critical of his teachings, but a number of western seekers have come to the end of their quest at his feet. For example, the Englishman John Levy wrote:

“I sought the truth and found my Lord and he showed me

my self. Seeing his form, hearing his words and

feeling his touch, I found my self. (...)

Not by wisdom alone was I shown the truth

but by endless love, for such is my Teacher,

Shri Atmananda.” 2

This text shows the completeness that Atmananda passed on. To express this completeness he often used the well-known expression Sat-Chit-Ananda, often translated by him as Existence, Knowledge and Peace – in other words, living, thinking and feeling in their essential nature, as the aspects that make up the complete Reality.

“I am not one who exists, but Existence itself (Sat).

I am not one who knows, but Knowledge itself (Chit).

I am not in peace but Peace itself (Ananda).” 3

Everyone is used to dealing with objects. ‘Object’ is a term for anything that presents itself to the senses; but thoughts and emotions are objects as well. We have been brought up being habituated with objects; this is so self-evident that hardly anyone wonders whether something is being skipped. We constantly are fascinated by a certain story, a shape, a subject, a memory, an idea, and so on. Those are all objects. Objects of something that itself is not an object at all. This ‘something’ is not a something, but to indicate it you must of course try to find a word for it, hence ‘something’ in quotation marks. All things that we experience or know, to which we give our attention, are the object of Knowing, or Consciousness.

Atmananda in his teachings constantly pointed out the relationship between ourselves and the objects, that is, between the Knowing and the objects of Knowing. For example, he once answered the question ‘What actually happens when you see a thing?’ as follows:

“When you say you see an object, you see only the dead part of the object. The Consciousness part, which alone is live, can never be seen.”4

The Consciousness part is that which bestowes reality to an object – hence it can be called alive. An object is only given reality and life when experiencing or knowing it.

“Therefore, the real ‘I’-Principle alone lives. The ignorant man believes that either the body or the mind lives, while in fact each of them dies at the end of every perception or thought. But the ‘I’-Principle continues unchanged through all thoughts and perceptions, lighting them up as well.” 5

The living is you. It is profound how Atmananda links your presence in the world with ‘bestowing life’, namely bestowing life and reality to the objects you are experiencing right now. He does not bow to the generally held habit of making the objective the most impressive, the grandest of what is called ‘creation.’ No, he praises the fact that you are now experiencing this creation, and you yourself are bringing it to life. If you did not experience this creation now, the whole ‘creation’ would remain an abstraction. Now you are experiencing objects, for example this article, the meaning of the previous sentence, the ‘I’ as a person who briefly appears as an apparent ‘subject’, the shape of these letters, this paper or computer screen, possibly the hand holding this paper, and so on – all objects.

But actually what is an object? Atmananda says:

“An object is there always pointing to the Consciousness (of the perceiver) as ‘You! You! You!’ – meaning thereby ‘I am here merely on account of you.’ But the moment you stand as Consciousness and turn back to the object, the object vanishes – in other words the object commits suicide.” 6

True life remains, which means Consciousness manifesting itself. Forms continue to emerge in this, but no longer as separate, self-contained realities, which could exist without Consciousness.

Everything in Atmananda’s teaching may come down to the fact that the forms that present themselves to us are a praise to the actual Experiencing of them. All those forms derive their existence from Experiencing. Form-in-itself does not actually exist. Form has a temporary existence or ‘life’ that lasts as long as form is known. The Experiencing or Knowing is never absent, and is therefore that which temporarily ‘gives life’ to the present object.

Objects are not an obstacle at all, Atmananda always emphasizes. They seem to distract us, but they only exist because of Consciousness, because of Knowing. Without being known they would not exist. Attempting to devote himself entirely to abiding in Pure Consciousness, Atmananda was once, in his years of training, distracted by the sound of a horse-and-carriage. He found it disturbing, and decided to sit somewhere else in order to devote himself more fully to recognizing Consciousness. But suddenly the thought occurred to him:

“Well, what nonsense! Is it not a means? What am I meditating upon, what am I contemplating? ‘I am pure Consciousness!’ Is it not so? And when that is so, even the noise that is heard there, does it not point to Me? (...) The noise that emanates from the horse-and-carriage helps me, points to Consciousness. (...) So then: ‘Come in, come in, come in! All disturbances: come in, come in! Quite all right! Help me, help me!’ So you see, nothing was a disturbance after that.” 7

However, Atmananda in his teaching and writing does not only use the phrasing just described, wherein the objects, thoughts, sense perceptions, etcetera are seen as pointing to Consciousness, or even ‘nothing other than Consciousness’. He often says that objects are completely different from Consciousness. This might be confusing to a reader. If you for instance read the chapters of his book Atma-Darshan one after the other, you can see that Atmananda seems in a way to dance between the two approaches, between differentiating and looking through the apparent difference. Sometimes even in the same chapter he dances to the other approach, with a logic that sometimes resembles a witticism. See, for example, how in Atma-Darshan, after emphasizing the distinction in chapters 3, 6 and 7 and the oneness in 1, 4, 5, 8 and 9, he says in verse 10 of chapter 10:

“It must be clearly understood that Consciousness is different from its object and that, while objects vary, Consciousness remains constant”;

after which he declares in verse 26 of the same chapter:

“Objects of Consciousness can never be separated from Consciousness itself. They have no independent existence. They are therefore nothing other than Consciousness.”

And so it goes on, in a sense, throughout the book. Is this confusing? At first it may seem so, but by really reading what the teacher says, really understanding what the meaning of the distinction is, and what is true in the ultimate sense (which means not being able to separate anymore because the ‘substance’ that makes up the objects being noticed as such), you will be able to see the value of this dance. If you never have noticed consciousness itself (often rightly capitalized as ‘Consciousness’) because it is never an object, it is very useful that you are being pointed out that consciousness itself can indeed be recognized and realized. Without being pointed out, it is possible that you keep looking over consciousness itself because of your habituation to objects. Atmananda himself says the following about the apparent two approaches:

“During the period of preliminary investigations in the study of Vedanta, you are asked to try to separate body and mind from the ‘I’-Principle. It is only to make you understand the relative values of the terms. Such a separation is not really possible; because, separated from the ‘I’-Principle, the other two do not exist at all. Therefore they are really nothing but the ‘I’-Principle. Vedanta asks you only to recognize this Truth.

From the position of Consciousness one can say that everything else is not. But from no position can you say that Consciousness is not. Because one has to be conscious of the Truth of that very statement before making it. Therefore Consciousness stands as the background of even that statement.

Hence even the statement that ‘Consciousness is not’ only proves that Consciousness IS. Therefore Consciousness is self-luminous and permanent.8

Training discernment is what this is all about. “While objects vary, Consciousness remains constant,” was just said in Atma-Darshan. That, in a way, is the first lesson in this enquiry: the discrimination between the changing and the unchanging. Recognize that all objects to which your attention is drawn, no matter how subtle they may be, always give way to the next object. They ‘change’ – you also can say that they dissolve to make room for the next object. You yourself make no room for anything else. You yourself turn out to be left without any change, and you notice that the previous object is no longer in your attention, and possibly that a current object seems to demand attention for a moment. This recognition of difference, this discrimination, is very important. This clearly shows that objects are in fact continuously passing through you, fleeting objects, and that something remains that is not an object at all, that is not fleeting. This simply remains the case regardless of the content of thoughts and feelings. It is not affected or weakened by that content; it just keeps on ‘illuminating it’ or ‘giving it light’. This is constant Knowing.

The fleeting as it is here called, is that which is described as ‘not real’ from Atmananda’s point of view. No matter how serious an object is to us, no matter how sensitive it is, from this point of view it is called unreal. Reality is something else.

“The test of the Reality is whether it disappears or not. According to this test, the only thing that never disappears is the ‘I’-Principle or ‘Consciousness’.” 9

So only the immutable is real. Everything else, anything that can be destroyed, is considered non-existent by Atmananda. Statements such as “Atma is the only Reality. Body is quite unreal” (Atma-Darshan chapter 10, verse 13) and “Therefore the world is not, has never been and is never going to be” (chapter 14, verse 4) could have an effect as if everything that the reader considers real and valuable is in one fell swoop wiped out as being ‘non-existent’. In this respect Atmananda was more radical than most teachers from the Advaita Vedanta tradition, at least from the ‘scholastic’ tradition (the non-scholastic tradition, with texts such as Yoga Vasishtha and Ashtavakra Gita, shows a radicality comparable to that of Atmananda10). Shankara, the eighth-century founder of the Advaita, was much more moderate in this respect, despite the fact that for many people he has become something of a symbol of the concept of maya – ‘illusion’. In fact, for Shankara and most of the later teachers, maya was a term for something inexplicable; it means, according to them, ‘neither being nor non-being’. Atmananda considered this maya view to be only for people who have not yet seen the real ‘I’, the real Subject. People who are established in the real ‘I’ have a ‘subjective standpoint’, by which he meant that the world is viewed exclusively from the changeless Consciousness, and that the world is recognized as Consciousness. For example, he said:

“But when one comes a step down from the subjective standpoint, some sort of an explanation may be needed for the world that appears there. It is in this way that the Maya theory has come in.” 11

People who have difficulty with the Maya view of ‘neither being nor non-being’, and especially with the view that the world ‘does not exist at all’, would do well to realize that we can never, in fact, escape Consciousness. No matter how you look at it, Consciousness is the condition for every aspect of our existence. It is therefore understandable that Atmananda’s enquiry does not go further into the question of what the material world actually is. His enquiry is only concerned with the question of what Reality is – and liberation from the idea of ‘unreality’. With his direct approach, he helps you to see the main point about liberation, which is the fact that Consciousness is always already free – and liberation in a deeper sense does not even exist because freedom is always already the case. This directness saves you all kinds of detours, all kinds of search movements. See, for example, how right away in the first chapter of Atma-Darshan Atmananda points to the ever-present, in the form of ‘water’, to show the immediacy of liberation. In that equation he says: “Waves are nothing but water. So is the sea” and “When water is realized, wave and sea vanish. What appeared as two is thus realized as one.” So one can see clearly that every method whereby a limited ‘I’ is seeking peace (like ‘waves seeking peace in the sea’) is completely indirect.

“Water can be reached straightway from wave by following the direct path. If the way through sea is taken, much more time is needed.” 12

Despite his radical stance in which ‘the world is non-existent’, Atmananda for many years simply fulfilled a function in the world of law enforcement. One should therefore not consider Atmananda’s standpoint as an attempt to deny or explain away something difficult. Dealing with the world and its objects was a very natural and justified matter for him.

“The Truth about this world is that the Reality, which is imperceptible to the senses, appears as this world when looked at through the senses. (...) The object of Vedanta is not to help you not to perceive the appearance, but to help you to see the essence even when perceiving the appearance through the senses.” 13

How can the seeing of this essence remain? Is it a matter of once seen, always seen, or is something like a so-called sadhana still needed? In general, Atmananda emphasized that a traditional sadhana, a preparation through all kinds of abstinence and so on, is not necessary. He himself had undergone such training, in the form of bhakti and raja yoga, but he often said that this is not really useful. The only advice that does contain a valid way of training is the direction he gives to repeatedly let the Truth sink in over and over again, to make direct understanding happen again and again. In other words, even if you have once really realized that Consciousness is constantly the case and that you yourself are nothing but That, in most cases there is still a need for a gradual infusion by this immediate understanding, just until it is irrefutable.14

It feels appropriate to give a personal testimony at the end of this article. As is well known, books can in most cases only provide a stepping stone to the realization of Reality. However, the repeated reading of Atma-Darshan and Atma-Nirvriti at a certain moment at the end of 1987, helped me to such an extent that from that moment on my life took on a different center of gravity. At that moment I got to know doubtlessness. While reading a specific chapter of Atma-Nirvriti, containing the sentences “I am pure happiness. All the activities of the sense-organs and the mind aim at happiness. So all these activities are a tribute (puja) to Me”,15 the bottom fell out of my belief in being a person, out of the belief that there is someone who could be set free. I have experienced that a text can have such an effect that after reading it you are never the same as before. Real clarity was bestowed to me, irreversibly. The living instructions of my teacher Alexander Smit (who had been a pupil of Atmananda-disciple Wolter Keers) had nourished me for a year and a half, especially with regard to the approach to Atmananda. And now I experienced Reality showing itself, without any reservations. Living itself remained, as Myself, and proved to be constant, even though the objects later sometimes took the form of doubt and fear again. The tilt of the center of gravity is not a tilt in person, form or manifestation. There is no one who has Understanding. The gratitude is what remains – eternally beginner, because nothing has ever been acquired, and nothing can ever be acquired. Thank you Gurunathan!

NOTES

1. Vedas are religious hymns from India, created between 1500-500 BC. They form the basis of many of the Indian religions and philosophies. Veda also means ‘knowledge’ or ‘knowing’; then Vedanta is ‘the end of knowledge.’ Advaita Vedanta, the non-dual way of Shri Atmananda, is the way of immediate seeing, or recognizing — ‘the direct way.’ Advaita means ‘non-duality’. The term Upanishad means ‘to sit at the feet of a teacher and listen to his words.’

2. John Levy, Immediate Knowledge and Happiness; 1st ed. p. 41, 42; 2nd ed. p. 69, 70. Levy’s second book, The Nature of Man According to the Vedanta, has contributed to the fact that the approach of Atmananda has become known in the West.

3. Notes on Spiritual Discourses of Sree Atmananda [hereafter mentioned as: Discourses] no. 1083 (p. 349); the order of the three terms in the text has been changed here to arrive at the usual order. Dutch teacher Wolter Keers writes in a note about Sat-Chit-Ananda somewhere: “These three words essentially mean exactly the same thing: the deepest and uninterrupted I-experience (not to be confused with the personality, ego or I-sense), denoted in terms which respectively indicate the background of living, thinking and feeling. It is like the description of one room by three people, looking in through different windows.” Ananda is usually translated Bliss or Happiness; Atmananda often translated it Peace. On the difference between the two terms, he said: “Happiness uninterrupted is Peace. Happiness is the first ebullition or sensation of Peace” (Discourses no. 654, p. 232). In other words, he regarded peace as the most essential designation of the feeling aspect (in Discourses no. 1335, p. 446: “Something called ‘Peace’, which is the source of all happiness”). In no. 740 (p. 258) Atmananda even introduces an improved version of the ancient expression, namely Sat-Chit-Shanta (shanti means peace; and shanta something like ‘come at peace; still’).

4. Discourses no. 483 (p. 181).

5. Discourses no. 43 (p. 19). The term ‘I’-Principle was Atmananda’s way of denoting the essential nature of ‘I’ — synonymous to him with the well-known term Atma, the ‘Self.’ In chapter 2 of ‘I’ is a Door’ I pay specific attention to Atmananda’s use of the term ‘I’-Principle.

6. Discourses no. 1402 (p. 476). The ‘committing suicide’ of the object refers to dissolving into Consciousness itself, or giving way to an entirely new object. Objects are not connected to each other.

7. Atmananda Tattwa Samhita, p. 186.

8. Discourses no. 390 (p. 147).

9. Discourses no. 48 (p. 22); see also no. 1055 (p. 339).

10. Atmananda quoted repeatedly from both texts. One of the few texts of the scholastic tradition from which he frequently quoted is the Pañchadashi, of the fourteenth-century Bharatitirtha-Vidyaranya.

11. Discourses no. 129 (p. 59); see also no. 1392 (p. 472).

12. Atma-Darshan, chapter 1, verse 8 (and verses 4 and 7).

13. Discourses no. 1114 (pp. 365, 366). Italics mine, PhR.

14. I consider the distinction between these two forms of training important. What I call here ‘traditional sadhana’ is a preparation for something in the future, and thus it acts as a condition. However, truth is without conditions and without time. Truth is instantly noticeable, always available. It is nevertheless necessary to ‘establish’ yourself in this again and again, because most people’s inclinations are filled with fascination and imagination, which obscure the Truth. “You have only to sense the Absolute through that eye of knowledge as often as possible, until you are securely established in the Ultimate” (Discourses no. 1065, p. 341).

15. Atma-Nirvriti, chapter 19, verse 1.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Atmananda (Krishna Menon), Atmananda Tattwa Samhita. The Direct Approach to Truth as Expounded by Sri Atmananda. Chengannur: Sri Vidya Samiti, 1973. Reprint: Austin, tx: Advaita Publishers, 1991.

Krishna Menon (Atmananda), Atma-Darshan. At the Ultimate. Tiruvannamalai: Sri Vidya Samiti, 1946. Reprint: Austin, tx: Advaita Publishers, 1989.

Krishna Menon (Atmananda), Atma-Nirvriti. (Freedom and Felicity in the Self). Trivandrum: Vedanta Publishers, 1952. Reprint: Austin, tx: Advaita Publishers, 1989.

Levy, John, Immediate Knowledge and Happiness. London: John Lloyd (John Watkins), 1951. Abridged second edition: London: Thorsons, 1970.

Levy, John, The Nature of Man According to the Vedanta. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1956.

Nair, M. P. Bhasi, Rays of the Ultimate. Santa Cruz, ca: sat, 1990.

Renard, Philip, ‘I’ is a

Door. The essence of Advaita as taught by Ramana Maharshi, Atmananda

(Krishna Menon) and Nisargadatta Maharaj, Mumbai: Zen Publications, 2017.

Tripta, Nitya, Notes on Spiritual Discourses of Sree Atmananda (of Trivandrum) 1950-1959. Trivandrum: Reddiar Press, 1963. Second edition, in three volumes, edited by Ananda Wood: Salisbury (uk): Non-Duality Press & Stillness Speaks, 2009 [pagination is from the original Indian edition]. In the Notes referred to as Discourses.

Dag Philip. Veel dank voor deze boeiende blog. Komt er ook een Nederlandstalige versie van je laatste post (Atmananda)? Groeten uit België

BeantwoordenVerwijderenBeste Belg (of Belgische), dank je voor je reactie. De oorsprong van deze tekst is Nederlands – het was een Inleiding in een boek dat helaas een publicatieverbod is opgelegd. Engelstaligen hebben het nooit kunnen lezen, vandaar dit Engels, in een versie die geheel losgekoppeld is van het boek. Maar door je vraag voel ik me aangespoord om toch ook een aangepaste Nederlandse versie te maken. Binnenkort zal ik hem hier plaatsen. Groeten uit Nederland!

VerwijderenI thank you for this enlightening article and in particular for your testimony in the last paragraph. It is essential to underline the importance that some writings can take on our path, especially when a living teaching is difficult to access.

VerwijderenHello Phillip this is Juan from Argentina … thanks for your writings … having read this story of Atmananda would like to ask if you can write about your master Alexander Smit.

BeantwoordenVerwijderenMy friend Robert Powell use to tell stories about Alexander and somehow developed a loving curiosity about him but unfortunately only found just scattered stories about his life.

Many thanks and warm regards

Juan Laguzzi

Google Translate

VerwijderenBeste Juan, sorry voor mij late reactie.

267 / 5.000

Dear Juan, sorry for my late response. This is a simple blog, and I don't spend much time on it. I don't get notified when there is a response. If you want to send me an email, I can try to write you something about Alexander personally. philip@advaya.nl

Feedback sturen