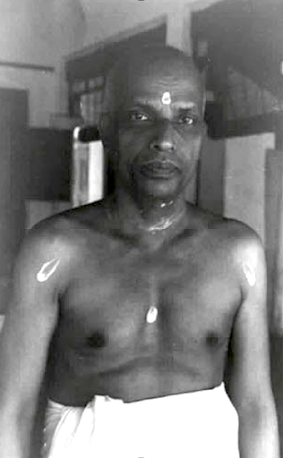

Shri Atmananda (Krishna Menon)

– een van de grootste leraren van de twintigste eeuw

door Philip Renard

(see also English translation)

Het is jammer dat tot op heden de grote Advaita-leraar Shri Atmananda (Shri Krishna Menon, door zijn discipelen Gurunathan genoemd) zo weinig bekendheid heeft gekregen. Voor velen is hij nog steeds een tamelijk onbekende figuur. Met dit artikel hoop ik te kunnen bijdragen aan de herkenning van hem als belangrijke bron voor direct Besef van de uiteindelijke Waarheid.

Twee kleine boeken van hem, Atma-Darshan en Atma-Nirvriti, vormen samen in feite een moderne Upanishad. Upanishads zijn klassieke teksten die sinds ongeveer de achtste eeuw voor onze jaartelling als slotgedeeltes werden toegevoegd aan de Veda’s. De term Vedānta (Veda-anta) duidt hierop; die betekent ‘het einde (anta) van de Veda’s’ en is een verwijzing naar de Upanishads.1 Een moderne Upanishad is een verzameling van zó stellige uitspraken dat de Vedanta-traditie als het ware opnieuw begint. Niet een commentaar op iets bestaands, maar een tekst die is voortgekomen uit huidig, ‘altijd vers’ Bewustzijn.

Shri Atmananda werd geboren als P. Krishna Menon op 8 december 1883, in Peringara, bij Tiruvalla, in Travancore (in de huidige Indiase deelstaat Kerala). Hij overleed op 14 mei 1959 in Trivandrum, de hoofdstad van Kerala. In de loop van zijn leven is hij voor veel mensen een waarachtig Leermeester geweest (een zogenaamde Karana Guru), ook voor een aantal westerlingen. Weliswaar waren sommige westerse intellectuelen die hem benaderden kritisch over zijn onderricht, maar een aantal westerse zoekers is aan zijn voeten aan het einde van hun zoektocht gekomen. Zo schreef bijvoorbeeld de Engelsman John Levy:

“Ik zocht de waarheid en vond mijn Heer

en hij toonde me mijn zelf. Bij het zien van zijn vorm,

het horen van zijn woorden en het voelen van zijn aanraking,

vond ik mezelf. (...)

Niet alleen door wijsheid werd me de waarheid getoond

maar door eindeloze liefde, want zo is mijn Leraar, Shri Atmananda.” 2

Dit tekstje toont de volledigheid die Atmananda doorgaf. Om deze volledigheid te verwoorden maakte hij vaak gebruik van de bekende uitdrukking Sat-Chit-Ananda, door hem vaak vertaald als Bestaan, Kennen en Vrede – met andere woorden: leven, denken en voelen in hun essentiële natuur, als de aspecten die samen de volledige Werkelijkheid vormen.

“Ik ben niet iemand die bestaat, maar Bestaan-op-zich (Sat).

Ik ben niet iemand die kent, maar Kennen-op-zich (Chit).

Ik ben niet iemand die in vrede is, maar Vrede-op-zich (Ananda).” 3

Iedereen is eraan gewend met objecten om te gaan. ‘Object’ is een term voor elk ding dat zich aan de zintuigen voordoet; maar ook innerlijke zaken zijn objecten. Met de gewenning aan objecten zijn we opgevoed; dit is zo vanzelfsprekend dat vrijwel niemand zich afvraagt of er niet iets wordt overgeslagen. Voortdurend zijn we geboeid door een bepaald onderwerp, een vorm, een verhaal, een herinnering, een idee, enzovoort. Dat zijn allemaal objecten. Objecten van iets dat zelf in het geheel geen object is. Dit ‘iets’ is juist geen iets, maar om het aan te duiden moet je natuurlijk toch taal proberen te vinden, vandaar een ‘iets’ tussen aanhalingstekens. Alle dingen die we meemaken of kennen, waaraan we onze aandacht geven, zijn object van het Kennen, oftewel Bewustzijn.

Atmananda wees in zijn onderricht voortdurend op de verhouding tussen onszelf en de objecten, oftewel tussen het Kennen en de objecten van het Kennen. Zo antwoordde hij bijvoorbeeld eens op de vraag “Wat gebeurt er eigenlijk als je een ding ziet?” als volgt:

“Wanneer je zegt dat je een object ziet, zie je alleen maar het dode deel van het object. Het Bewustzijns-deel, dat het enige deel is dat levend is, kan nooit worden gezien.” 4

Het Bewustzijns-deel is datgene wat werkelijkheid schenkt aan een object – vandaar dat dat levend genoemd kan worden. Een object wordt alleen tijdens het meemaken of kennen ervan werkelijkheid en leven geschonken.

“Daarom is het enige dat leeft het werkelijke ‘Ik-Beginsel’. De niet-beseffende mens gelooft dat het lichaam en de geest leven, maar deze sterven in feite allebei steeds aan het einde van iedere waarneming of gedachte. Wat zonder enige verandering continueert is het Ik-Beginsel, door alle waarnemingen en gedachten heen – waarbij het deze doet oplichten.” 5

Het levende ben Jij. Het is diepgaand, hoe Atmananda je aanwezigheid in de wereld koppelt aan ‘leven schenken’, namelijk het leven schenken aan de objecten die je nu meemaakt. Hij buigt niet voor de algemeen gehuldigde gewoonte om het objectieve tot het meest indrukwekkende te maken, het grootse van wat ‘de schepping’ wordt genoemd. Nee, hij roemt het feit dat jij nu deze schepping meemaakt en daardoor tot leven brengt. Als jij nu deze schepping niet zou meemaken, zou de hele ‘schepping’ een abstractie blijven. Nu maak je objecten mee, bijvoorbeeld dit artikel, de betekenis van de voorgaande zin, het ‘ik’ als persoon die even als schijnbaar ‘subject’ opkomt, deze letters, dit papier of beeldscherm, eventueel de hand die dit papier vasthoudt, enzovoort – allemaal objecten.

Maar wat is een object eigenlijk? Atmananda zegt:

“Een object is constant wijzend naar Bewustzijn (de Waarnemer) als ‘Jij! Jij! Jij!’ – daarmee implicerend: ‘ik ben hier uitsluitend dankzij Jou.’ Op het moment dat jij je als Bewustzijn opstelt, en je weer wendt tot het object, verdwijnt het object – met andere woorden, het object pleegt zelfmoord.” 6

Het ware leven blijft over, namelijk dat wat het leven Leven schenkt, oftewel Licht schenkt. Vormen blijven hierin opkomen, maar niet meer als afzonderlijke, zelfstandige realiteiten, die zonder Bewustzijn zouden kunnen bestaan.

Alles in Atmananda’s onderricht komt er wellicht op neer dat de vormen die zich aan ons aandienen een lofzang zijn op het Meemakende, het Belevende. Al die vormen ontlenen hun bestaan aan het Belevende, oftewel Beleving. Vorm-op-zich bestaat eigenlijk niet. Vorm heeft een tijdelijk bestaan of ‘leven’ dat duurt zolang vorm gekend wordt. Het Belevende of Kennende is nooit afwezig, en is daardoor dat wat tijdelijk leven schenkt aan huidig object.

Objecten zijn helemaal geen hindernis, zo benadrukt Atmananda steeds. Zij lijken ons wel af te leiden, maar ze bestaan alleen maar dankzij Bewustzijn, dankzij Kennen. Zonder gekend te worden zouden ze er niet zijn. Bij een poging om zich helemaal te wijden aan het vertoeven in Puur Bewustzijn werd Atmananda ooit, in de jaren waarin hij nog een training onderging, afgeleid door het geluid van een paard-en-wagen. Hij ervoer het als storend, en besloot ergens anders te gaan zitten om zich beter te kunnen wijden aan het herkennen van Bewustzijn. Maar opeens kwam hij tot het besef:

“Wat een onzin! Is dit lawaai niet juist een hulpmiddel? Waar ben ik nou op aan het mediteren? ‘Ik ben louter Bewustzijn’, is het niet? En als dat zo is, wijst dan ook het lawaai dat je hier hoort niet naar Mij? (...) Het lawaai dat van de paard-en-wagen komt, helpt me, want het wijst naar Bewustzijn. (...) Dus zei ik: ‘Kom erin, kom erin! Alle verstoringen: kom binnen! Kom binnen! Helemaal goed! Help me, help me!’ Daarna was niets meer een verstoring.” 7

Wie door het boek Atma-Darshan bladert, zal kunnen opmerken dat Atmananda hierin niet voortdurend de benadering naar voren brengt die zojuist beschreven werd, de benadering waarbij de objecten, gedachten, zintuiglijke waarnemingen enzovoort gezien worden als vervat in, of verwijzend naar Bewustzijn, of ‘niets anders te zijn dan’ Bewustzijn. Vaak benadrukt hij juist dat objecten geheel verschillend zijn van Bewustzijn. Dit kan verwarrend werken op een lezer. Als je de hoofdstukken na elkaar leest, kun je zien dat Atmananda op een bepaalde manier lijkt te dansen tussen beide benaderingen, tussen onderscheid-maken en heenkijken-door-schijnbaar-verschil. Soms danst hij in hetzelfde hoofdstuk naar de andere benadering, met een logica die wel eens op een kwinkslag lijkt. Zie bijvoorbeeld hoe hij in Atma-Darshan, na het onderscheid te hebben benadrukt in de hoofdstukken 3, 6 en 7 en de eenheid in 1, 4, 5, 8 en 9, in hoofdstuk 10 (in vers 10) zegt:

“Je dient duidelijk te begrijpen dat Bewustzijn verschillend is van zijn objecten – terwijl objecten veranderen, blijft Bewustzijn onveranderlijk”;

waarna hij in vers 26 van hetzelfde hoofdstuk meldt:

“Wat object van Bewustzijn is, kan nooit worden gescheiden van Bewustzijn zelf. Objecten hebben geen onafhankelijk bestaan. Daarom zijn ze niets anders dan Bewustzijn.”

En zo gaat het in zekere zin het hele boek door.

Is dit verwarrend? Aanvankelijk lijkt dat wel zo, maar door echt te lezen wat de leraar zegt, echt te verstaan wat de zin is van het onderscheid, en wat in uiteindelijke zin waar is, namelijk het niet meer kunnen scheiden omdat het ‘spul’ of de ‘substantie’ waaruit de objecten bestaan als zodanig wordt opgemerkt, zul je kunnen zien wat de waarde van deze dans is. Als je nooit bewustzijn op zich (terecht vaak als Bewustzijn gespeld) hebt opgemerkt, omdat dat nooit een object is, is het zeer zinvol dat je erop gewezen wordt dat bewustzijn op zich wel degelijk opgemerkt of beseft kan worden. Zonder hier op gewezen te worden kan het zijn dat je vanwege je gewend zijn aan objecten ‘over bewustzijn heen blijft kijken’. Atmananda zegt over de twee benaderingen zelf het volgende:

“In de periode waarin je in de Vedanta voor het eerst onderzoek doet, wordt je gevraagd lichaam en geest te scheiden van het Ik-Beginsel. Dat is om goed de betekenis van de respectievelijke termen in hun ware verhouding te kunnen zien. In werkelijkheid is zo’n scheiding echter niet mogelijk, omdat lichaam en geest niet kunnen bestaan als ze gescheiden zouden zijn van het Ik-Beginsel. Daarom zijn ze in feite niets anders dan het Ik-Beginsel. Vedanta vraagt je alleen maar deze Waarheid te herkennen.

Vanuit het gezichtspunt van Bewustzijn kun je zeggen dat al het andere er niet is, maar vanuit geen enkel gezichtspunt kun je zeggen dat Bewustzijn er niet is. Je moet je immers bewust zijn van de Waarheid van deze bewering voordat je dit kunt zeggen. Zo blijkt Bewustzijn de ‘ondergrond’ te zijn, zelfs van deze uitspraak.

Vandaar dat ook de bewering dat ‘Bewustzijn niet is’ alleen maar bewijst dat Bewustzijn IS. Hieruit blijkt duidelijk dat Bewustzijn vanuit-zichzelf licht-schenkend is – permanent.” 8

Het trainen van het onderscheidingsvermogen is waar het hier om gaat. “Terwijl objecten veranderen, blijft Bewustzijn onveranderlijk”, werd zojuist in Atma-Darshan gezegd. Dat is op een bepaalde manier de eerste les bij dit onderzoek: het onderscheid tussen het veranderende en het onveranderlijke. Herken dat alle objecten waar je aandacht naartoe gaat, hoe subtiel die ook zijn, steeds wijken voor een volgend object. Ze ‘veranderen’ – je kunt ook zeggen dat ze oplossen om plaats te maken voor een volgend object. Jij zelf maakt geen plaats voor iets anders. Jij blijkt over te blijven, zonder enige verandering te hebben ondergaan, en jij merkt op dat het vorige object niet meer in je aandacht is, en dat een huidig object voor een moment aandacht lijkt te vragen. Dit herkennen van verschil, dit onderscheiden, is belangrijk. Dit laat helder zien dat er eigenlijk steeds objecten door je heen gaan, vluchtige, vlietende objecten, en dat iets aanwezig blijft dat helemaal geen object is, dat niet vlietend is. Dit blijft gewoon constant het geval, hoe de inhoud van het denken en voelen ook is. Het wordt door die inhoud niet aangetast of verzwakt; het blijft gewoon ‘verlichten’ of ‘licht schenken’. Dit is constant Kennen.

Het vlietende zoals het hier wordt genoemd, is datgene wat vanuit Atmananda’s gezichtspunt beschreven wordt als ‘niet werkelijk’. Hoe serieus een object ook voor ons is, hoe gevoelig het ook ligt, vanuit dit gezichtspunt wordt het onwerkelijk genoemd. Werkelijkheid is iets anders.

“De test van de Werkelijkheid is of het verdwijnt of niet. Het enige dat volgens deze test nooit verdwijnt is het ‘Ik-Beginsel’ oftewel Bewustzijn.” 9

Alleen het onveranderlijke en onafhankelijke is dus echt, of werkelijk. Al het andere, alles wat vernietigd kan worden, wordt door Atmananda beschouwd als niet-bestaand. Uitspraken zoals “Atma is de enige Werkelijkheid; het lichaam op zich is in feite onwerkelijk” (Atma-Darshan hoofdstuk 10, vers 13) en “Daarom is er geen wereld – die is er nooit geweest, en zal nooit bestaan” (hoofdstuk 14, vers 4), kunnen op de lezer een werking hebben alsof alles wat als echt en waardevol beschouwd wordt, in één klap weggevaagd wordt als zijnde ‘niet-bestaand’.

Atmananda was wat dit betreft radicaler dan de meeste leraren uit de traditie van de Advaita Vedanta, althans uit de ‘schoolse’ traditie (de niet-schoolse traditie, met teksten als Yoga Vasishtha en Ashtavakra Gita, vertoont een radicaliteit die vergelijkbaar is met die van Atmananda10). Shankara, de achtste-eeuwse grondlegger van de Advaita, was in dit opzicht veel gematigder, ondanks het feit dat hij voor veel mensen een soort symbool is geworden van het begrip maya – ‘illusie’. In feite was maya voor Shankara en de meeste van de latere leraren een term voor iets dat niet valt te verklaren; het is volgens hen ‘zijn noch niet-zijn’. Atmananda beschouwde deze maya-visie als alleen maar bedoeld voor mensen die nog geen oog hebben voor het ware Ik, het werkelijke Subject. Mensen die in het ware Ik gegrondvest zijn, hebben een ‘subjectief gezichtspunt’, waarmee hij bedoelde dat de wereld uitsluitend beschouwd wordt vanuit het onveranderlijke Bewustzijn, en dat de wereld herkend wordt als Bewustzijn. Zo zei hij:

“Maar als je een treetje lager gaat dan het subjectieve gezichtspunt, heb je de een of andere uitleg nodig voor de wereld die daar verschijnt. Op deze manier is de maya-theorie geïntroduceerd.” 11

Mensen die moeite hebben met de maya-visie van ‘zijn noch niet-zijn’, en zeker met het standpunt dat de wereld ‘helemaal niet bestaat’, doen er goed aan zich te realiseren dat we in feite nooit aan Bewustzijn kunnen ontsnappen. Hoe we ons ook wenden of keren, Bewustzijn is de voorwaarde voor ieder aspect van ons bestaan. Daarom voelt het terecht dat Atmananda’s onderzoek niet verder ingaat op de vraag wat de materiële wereld dan wél is. In zijn onderzoek gaat het alleen maar om de vraag wat Werkelijkheid is, en bevrijding uit onwerkelijkheid. Met zijn directe benadering helpt hij je om de hoofdzaak over bevrijding te zien, namelijk het feit dat Bewustzijn altijd al vrij is (en daarmee eigenlijk dat ‘bevrijding’ niet eens bestaat omdat vrijheid altijd al het geval is). Hij bespaart je daarmee allerlei omwegen, allerlei zoekbewegingen.

Zie bijvoorbeeld hoe hij al meteen in het eerste hoofdstuk van Atma-Darshan het altijd-aanwezige (daar ‘water’ genoemd) laat optreden om de onmiddellijkheid van bevrijding te laten zien. In die vergelijking zegt hij:

“Golven zijn niets anders dan water. De zee is ook niets anders dan water. Precies zo zijn zowel het individu als God niets anders dan Zijn, Bewustzijn, Vrede”; en:

“Wanneer in zowel golf als zee water wordt herkend, verdwijnen ze allebei. Wat twee scheen wordt nu gerealiseerd als één.”

In deze vergelijking kun je heel duidelijk zien dat iedere methode waarbij een beperkt ‘ik’ vrede zoekt (als ‘golven die rust en vrede zoeken in de zee’) volstrekt indirect is.

Water kan onmiddellijk vanuit de golf gevonden worden door het volgen van de directe weg. Wanneer de weg via de zee wordt genomen, is veel meer tijd nodig.” 12

Ondanks zijn radicale standpunt waarin ‘er geen wereld is’, vervulde Atmananda jarenlang gewoon een functie in de wereld van politie en justitie. Men moet Atmananda’s standpunt dan ook niet zien als een poging om iets lastigs te ontkennen of weg te redeneren. Omgaan met de wereld en zijn objecten was voor hem een heel vanzelfsprekende en terechte aangelegenheid.

“De Waarheid over deze wereld is dat de Werkelijkheid, die zintuiglijk niet waarneembaar is, zich als deze wereld voordoet wanneer er met de zintuigen waargenomen wordt. (...)

Het doel van de Vedanta is niet om je te verhinderen objecten te zien, maar om je te helpen de essentie te zien terwijl je de verschijning via de zintuigen opmerkt.” 13

Hoe kun je deze essentie blijven zien? Is dat een kwestie van eenmaal gezien, altijd gezien, of is er nog zoiets als een training of sadhana nodig?

In het algemeen benadrukte Atmananda dat een ouderwetse sadhana, een voorbereiding door middel van allerlei onthoudingen enzovoort, niet nodig is. Zelf had hij een dergelijke training wel ondergaan, in de vorm van bhakti en raja yoga, maar hij zei steeds dat dit eigenlijk niet zinnig is. Het enige advies dat wel een element van training bevat, is de aanwijzing die hij herhaaldelijk geeft (ook in het huidige boek) om de Waarheid steeds weer tot je door te laten dringen, om Besef opnieuw en opnieuw te laten gebeuren. Met andere woorden, ook al heb je eens werkelijk beseft dat Bewustzijn constant het geval is en dat jij zelf niets anders bent dan Dat, het is in de meeste gevallen zo dat er nog een geleidelijke inwerking nodig is van dit onmiddellijke Besef, net zo lang tot het onomstotelijk is.14

Het voelt op zijn plaats om aan het slot van dit artikel een persoonlijke getuigenis af te leggen. Boeken kunnen in de meeste gevallen slechts een opstapje bieden naar het Besef van de Werkelijkheid. Het boek Atma-Nirvriti echter heeft mij op een gegeven moment, in de winter van 1987 op ’88, een zodanige hulp geboden dat mijn leven vanaf dat moment een ander zwaartepunt heeft gekregen. Ik heb toen twijfelloosheid leren kennen. Door het lezen van de tekst ‘Het eerbetoon van zintuigen, denken en voelen aan Mij’ (hoofdstuk 19), met daarin de zinnen

“Ik ben puur Geluk.

Alle activiteiten van zintuigen, denken en voelen

hebben geluk als doel.

Dus al deze activiteiten zijn een eerbetoon aan Mij”,15

viel ik uit mijn geloof in de persoon, uit het geloof dat er iemand is die bevrijd zou kunnen worden. Ik heb ondervonden dat een tekst een zodanige werking kan hebben dat je na lezing ervan nooit meer dezelfde bent als daarvoor. Waarachtig Besef werd me geschonken. Het levende onderricht van mijn leraar Alexander Smit had me anderhalf jaar gevoed, juist ook wat betreft de benadering van Atmananda. En nu maakte ik mee dat de Werkelijkheid zich toonde, zonder enig voorbehoud. Het Levende bleef over, als Ikzelf, en bleek constant te zijn, ook al hadden de objecten later soms ook weer de vorm van twijfel en angst. De kanteling van zwaartepunt is niet een kanteling in de persoon, in de vorm of manifestatie.

Er is niet iemand die Besef heeft. De dank is wat overblijft – eeuwig beginner, omdat nooit iets is verworven, en nooit iets te verwerven valt. Dank u, Gurunathan!

NOTEN

1. Veda’s zijn religieuze hymnen uit India, ontstaan tussen 1500-500 vC. Zij vormen de basis van veel van de Indiase religies en filosofieën. Veda betekent ook ‘kennis’ of ‘weten’; dan is Vedanta ‘het einde van het weten’. Advaita Vedanta, de non-dualistische weg van Shri Atmananda, is de weg van het onmiddellijke zien, oftewel herkennen – ‘de directe weg’. Advaita betekent non-dualiteit. De term Upanishad betekent ‘het zitten aan de voeten van een leermeester om te luisteren naar diens woorden’.

2. John Levy, Immediate Knowledge and Happiness; 1e ed. p. 41, 42; 2e ed. p. 69, 70. Levy’s tweede boek, The Nature of Man According to the Vedanta, dat later ook in het Nederlands werd uitgegeven (Het wezen van de mens volgens de Vedanta, in tweede druk getiteld Non-dualiteit), heeft ertoe bijgedragen dat de benadering van Atmananda ook in Nederland bekend is geworden.

3. Notes on Spiritual Discourses of Sree Atmananda [hierna aangeduid als Discourses] No. 1083 (p. 349); de volgorde van de drie termen in de tekst is hier gewijzigd om te komen tot de gebruikelijke volgorde. Wolter Keers schrijft ergens in een noot over Sat-Chit-Ananda: “Deze drie woorden betekenen in wezen precies hetzelfde: de diepste en ononderbroken IK-ervaring (niet te verwarren met de persoonlijkheid, het ego of ik-gevoel), aangeduid in termen die respectievelijk de achtergrond aanduiden van leven, denken en voelen. Het is als de beschrijving van één vertrek door drie personen, die door verschillende ramen naar binnen kijken.” Ananda wordt meestal met Gelukzaligheid of Geluk vertaald; Atmananda vertaalde het vaak met Vrede. Over het verschil tussen beide termen zei hij: “Geluk dat ononderbroken is, is Vrede. Geluk is de eerste opborreling of sensatie van Vrede”; Discourses No. 654 (p. 232). Vrede beschouwde hij met andere woorden als de meest essentiële aanduiding van het gevoelsaspect (in Discourses No. 1335, p. 446: “Iets genaamd ‘Vrede’, dat de bron is van alle geluk”). In No. 740 (p. 258) introduceert Atmananda zelfs een verbeterde versie van de oeroude uitdrukking, namelijk Sat-Chit-Shanta (shanti betekent vrede; en shanta zoiets als ‘tot vrede gekomen; stil’).

4. Discourses No. 483 (p. 181).

5. Discourses No. 43 (p. 19). De term ‘Ik-Beginsel’ was Atmananda’s manier om de wezenlijke natuur van ‘ik’ aan te geven – voor hem synoniem van de bekende term Atma, het ‘Zelf’. In hoofdstuk 2 van ‘Ik’ is een deur besteed ik aandacht aan Atmananda’s gebruik van de term ‘Ik-Beginsel’.

6. Discourses No. 1402 (p. 476). Het ‘zelfmoord plegen’ van het object verwijst naar het oplossen in Bewustzijn op zich, of plaatsmaken voor een volledig nieuw object. Objecten hebben geen verbinding met elkaar.

7. Atmananda Tattwa Samhita, p. 186.

8. Discourses No. 390 (p. 147).

9. Discourses No. 48 en 1055 (p. 22 en 339).

10. Uit beide teksten citeerde Atmananda herhaaldelijk. Een van de weinige teksten uit de schoolse traditie waaruit hij veelvuldig citeerde is de Pañchadashi, van de veertiende-eeuwse Bharatitirtha-Vidyaranya.

11. Discourses No. 129 (p. 59); zie ook No. 1392 (p. 472).

12. Atma-Darshan, hoofdstuk 1, vers 8 (en verzen 4 en 7).

13. Discourses No. 1114 (p. 365, 366). Cursivering van mij, PhR.

14. Het onderscheid tussen deze beide vormen van training beschouw ik als belangrijk. Wat ik hier ‘ouderwetse sadhana’ noem is een voorbereiding op iets, en daardoor werkt het als een voorwaarde. Waarheid is echter zonder voorwaarden. Waarheid is direct opmerkbaar, altijd beschikbaar. Het keer op keer jezelf ‘grondvesten’ hierin is desondanks nodig, omdat de geneigdheden van de meeste mensen vervuld zijn van fascinatie en verbeelding, die de Waarheid verhullen. “Wat je te doen hebt is alleen maar zo vaak mogelijk het Absolute gewaar te worden met het ‘oog van Besef’, tot je onwankelbaar gegrondvest bent in het Uiteindelijke” (Discourses No. 1065, p. 341).

15. Atma-Nirvriti, hoofdstuk 19, vers 1.

BIBLIOGRAfie

Atmananda (Krishna Menon), Atmananda Tattwa Samhita. The Direct Approach to Truth as Expounded by Sri Atmananda. Chengannur: Sri Vidya Samiti, 1973. Herdruk: Austin, tx: Advaita Publishers, 1991.

Krishna Menon (Atmananda), Atma-Darshan. At the Ultimate. Tiruvannamalai: Sri Vidya Samiti, 1946. Herdruk: Austin, tx: Advaita Publishers, 1989.

Krishna Menon (Atmananda), Atma-Nirvriti (Freedom and Felicity in the Self). Trivandrum: Vedanta Publishers, 1952. Herdruk: Austin, tx: Advaita Publishers, 1989.

Levy, John, Immediate Knowledge and Happiness. Londen: John Lloyd (John Watkins), 1951. Verkorte tweede editie: Londen: Thorsons, 1970.

Levy, John, The Nature of Man According to the Vedanta. Londen: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1956. Ned. vert.: Het wezen van de mens volgens de Vedanta. Haarlem: Stichting Yoga Nederland, z.j. [1972]; vertaler: N.G. van der Pas. Tweede editie: Non-dualiteit. Het wezen van de mens volgens de Advaita Vedanta. Heemstede: Altamira, 1992.

Nair, M. P. Bhasi, Rays of the Ultimate. Santa Cruz, ca: sat, 1990 [bevat veel interessante details over het leven in de nabijheid van Atmananda].

Renard, Philip, ‘Ik’ is een deur. Over de ingang die geboden wordt door de Grote Drie van de twintigste-eeuwse Advaita: Ramana Maharshi, Atmananda (Krishna Menon) en Nisargadatta Maharaj. Rotterdam: Asoka, 2008. Eng. vert.: ‘I’ is a Door. Mumbai: Zen Publications, 2017.

Renard, Philip, Bevrijding – dankzij het ontwaren van verschil en het Verschilloze. De essentie van de Advaita-geschriften Viveka Chudamani (Het ware onderscheid als kroonjuweel) en Atma Bodha (Besef van Zelf). Amsterdam: Samsara, 2022 [bevat verschillende commentaren van Atmananda].

Tripta, Nitya, Notes on Spiritual Discourses of Sree Atmananda (of Trivandrum) 1950-1959. Trivandrum: Reddiar Press, 1963. Tweede editie, in drie delen, geredigeerd door Ananda Wood: Salisbury (uk): Non-Duality Press & Stillness Speaks, 2009 [paginering is van de originele Indiase editie]. In de Noten aangeduid als Discourses.