The ‘Simultaneous’ Triangle of Dzogchen

(zie de Nederlandse tekst)

by Philip Renard

Within Tibetan Buddhism, Dzogchen occupies a position

that you can call ‘the highest’. Literally it means ‘Great (chen)

Completeness (dzog)’. Dzog also means ‘completion’, ‘perfection’,

‘finishing’. In other words: ‘you will come to your end’. You cannot go further

or higher.

For

me, Dzogchen, as it reached me since the mid-1980s mainly thanks to Namkhai

Norbu, is one of the clearest expressions of reality. Over the years, many

details of this teaching have crystallized in me, especially through the words

of Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche. So much so that I dare say that his form of teaching,

based on the radical words of the great fourteenth-century teacher Longchenpa,

has in recent years been the most important inspiration for what I myself pass

on to others.

Tulku

Urgyen uses what I call a ‘stamp’ style in his speech. By that I mean he

basically says the same thing over and over. The stamp remains the same stamp,

and it always lands identically, at exactly the same spot. I often think of the

well-known story about the drop of water that keeps falling on a stone, at

exactly the same place. The story goes that the stone actually gets pierced, no

matter how hard it is. So by simply continuing to stamp, the opening is

provided.

What

is it that Tulku Urgyen keeps saying over and over?

His

emphasis is as follows. It’s all about recognizing: recognizing your

true nature and learning to become stabilized in the recognition. For most

people a one-time recognition is not enough – the chain of karmic tendencies

can repeatedly obscure the view. Hence Tulku Urgyen says:

“In this entire world, there is nothing superior to

or more precious than knowing how to break this chain.” [1]

Yes, how do you get a true insight into this, how

do you break this chain? First of all, whatever your current situation

or state of mind is, recognize what your essential, original nature is, in

the midst of your current situation. At the moment of actual recognition

there is an opening, an interruption. No more trains of thought, no story in

which you are lured to the next fascinating detail. Here is the most profound

invitation: leave your story for now, and look, allow this opening to

sink in. You will then easily see that this is ‘no-thing’. Tulku Urgyen

repeatedly says about this: “Seeing no thing is the supreme sight.” [2]

You can also immediately see that this is indeed ‘yourself’. For you can

immediately recognize that this no-thing is seen, that is, there is a continuous

knowing principle – even though it is not an entity. It is precisely the

combination of these two factors, seeing and no-thing, that causes neither of

them to get the upper hand, one to nihilism, the other to taking a position,

that is, identification with a subtle Something or Someone. The Advaitic

statement ‘I am Brahman’ is here replaced by ‘I realize that my essential

nature is No-thing – naked Knowing.’

In

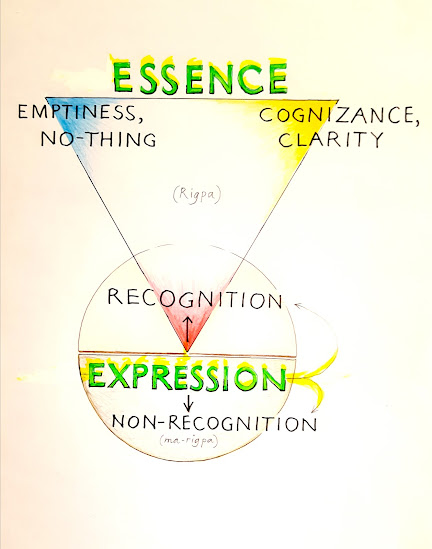

Dzogchen, our essential nature is described as consisting of the following three

aspects:

1. empty,

conceptless essence

2. clear, cognizing

nature

3. unconfined,

unobstructed expression

There are many triads in Tibetan Buddhism, but

these three aspects make up the golden triad for me: unconfined empty

cognizance. Everything is contained in this. Because I was so deeply moved by

the simplicity of this trio, I started making drawings of it over the years,

whereby the trio became a triangle. It is an equilateral or ‘simultaneous’

[3] triangle. The equilateral (and simultaneous) feels justifiable

because all three aspects are ultimately equally important, even though

the trio contains a hierarchical element. The point in it is mainly that it is

about full inclusiveness. I would like to elucidate the three aspects just

mentioned here a little bit.

1.

First of all, the ‘essence’ (in Tibetan ngo-bo).

The essence is just the essence, so you can’t say ‘the essence of the essence’

afterwards. No. It stops. That is exactly the function of this kind of

language. The essence is immediately named as Emptiness (stong-pa

nyid). Emptiness knocks all knowledge out of your hands, everything is

taken away from you. So IT S T O P S – and that is the blessing. No-mind,

No-thing and Emptiness mean the same thing to me. All emphasis here is on the termination

of all concepts, of all mental and emotional structures, no matter how noble.

In this respect even ‘love’ is a concept, and thus follows hierarchically only

as one of the examples of the third aspect, being the expression of the

essence.

2.

This essence is inseparable from the cognizing

principle, which is also referred to as Clarity (in Tibetan gsal-ba),

and often as Luminosity and Lucidity. Beautiful indications, I think. It is the

cognizing or knowing principle that matters – Awareness as such. You may say

that the empty essence is the heart of the matter, but without the knowing

principle you do nothing. In Dzogchen it is therefore emphasized that emptiness

must always be knowing, otherwise you will get negative interpretations of the

word ‘empty’ – from here many Vedantic prejudices against the Buddhists have

arisen. In my view, Buddhism only became a real direct path of

liberation when balance was found in China around the fifth century, by

recognizing that everything and everyone is not only empty (which was

the emphasis until then), but also has a true nature which is knowing. Dharmakshema,

translator of the Nirvana Sutra into Chinese, called it ‘Buddha-nature’

(fo xing) [4]: it concerns the inseparability of no-thought

(empty) and awareness (‘light-bestowing’) – in your actual presence.[5]

The

unity of empty essence and cognizing nature is the same as what in Advaita

Vedanta is called the ‘qualityless Absolute’. Apparently there are two

here, especially if you picture it, but in fact the concepts of empty and cognizing

together form the most complete and inclusive designation for the ineffability

of the Ultimate. They are respectively the negative and the positive way of

denoting, and thus they let you feel the Great Completeness immediately – the

idea of ‘two’ completely disappearing. This is how you descry Non-difference;

there really isn’t any difference to be found here.

This

is called Rigpa in Dzogchen, Empty Awareness. The inseparable unity of

No-thing and Knowing. You can consider Rigpa as the most important in

Dzogchen. The point that matters.

3.

The unity of No-knowledge and Knowing (or Emptiness

and Awareness) is consistently described as inseparable and uninterrupted,

allowing for an expression that is completely unobstructed (in Tibetan ’gags-med).

Because there is no obstruction or obstacle, the expression occurs immediately;

there is no such thing as a time difference yet – time arises precisely

here. In this approach there has never been a Fall.

The

third aspect entirely concerns this Expression of the Empty Awareness – that

is, its manifestation. An indication such as ‘the core of the matter’ can still

remain abstract, as some ‘knowledge’, but as soon as the core manifests

itself abstraction cannot remain. The Tibetan word for this aspect is thugs-rje.

In Dzogchen this term is interpreted as ‘capacity’, ‘resonance’,

‘responsiveness’ – and also ‘energy’. Thanks to the capacity of Awareness there

can be manifestation, presence, experience.

There

is in fact not yet any difference between Emptiness and Awareness, but as soon

as this Non-difference comes into manifestation, difference is born (and

time, and cause-and-effect), and with lightning speed there is also the

possibility of the difference between freedom and non-freedom, between reality

and illusion. As soon as you are, and experience, preference can

set in, and possibly a getting stuck. A moment ago there was still freedom, and

suddenly there is something that triggers, so that you can become completely

occupied, and glued to an emotionally tinted story. It feels like a primal

split, in which fortunately the question can arise again and again: What do I

really want? Do I want true freedom, or do I actually just want to take it easy

and have fun and pleasure?

Nisargadatta

Maharaj has devoted much of his teaching to clarifying this point of ‘the

manifest,’ which he often referred to as ‘I am’ or the birth principle. There

is no question here of a person or individual, but of experience-in-itself – in

which the primal split takes place, which is based on the chain of karmic

inclinations mentioned. I once sketched this primordial split in a circular

shape, like a pill with two halves.[6] Tulku Urgyen called it

a ‘fork in the road’.[7] Do you want to come to realization,

or do you leave it at that, and continue to live a life that essentially

amounts to non-realization?

When drawing the triangle, at a certain point I

decided to add the drawing of the crossroads circle. After all, once you start

expressing yourself, duality is a given. If there were only the essence, then

of course nothing needs to be investigated in order to arrive at liberation.

The essence, Empty Awareness, is always already free. There is nothing to

achieve in this. It is about realizing this naked Awareness in your

present existence, in the midst of your own expression, however confusing it

may be. Your thoughts and emotions must be seen through as nothing but a

temporary expression of your innate timeless nature. So: recognize the

empty essence within your thoughts and emotions.

With

the combination of triangle and circle you can show the connection between the

essence and its expression. On the drawing this is emphasized as a pair in

capital letters. Tulku Urgyen has spoken about this repeatedly, including the

crossroads character contained in the phrase:

“The only possibility of recognition lies in the

expression. The expression (rtsal) of this essence (ngo-bo)

can either know itself or not know itself, that is the whole importance of

knowledge – in Sanskrit, prajña, in Tibetan, sherab. It is said

that when the expression dawns as sherab, as knowledge – when the

expression knows its own nature – it is liberated, there is freedom. When the

expression moves as thought, as thinking, it is bewildered – there is delusion.

In this distinction lies the whole difference. In other words, whether the

expression is liberated as knowledge or confused as thinking is determined by

the practitioner knowing or not knowing his own nature.” [8]

To me, this is the core of all teaching. By

actually allowing this key point into your life, the karmic chain will be

broken. This emphasis contains the whole matter, completely and directly,

without any accumulated knowledge. May this emphasis, possibly with the help of

triangle & circle, work as a true stamp. May the stamp fall again and

again, brand new, at a receptive spot.

NOTES

1. Tulku Urgyen, As It Is, Vol. I (Rangjung Yeshe, Boudhanath 1999);

p. 75.

2. See, for example, As It Is, Vol. II (Rangjung Yeshe, Boudhanath, 2000);

p. 76.

3. ‘Simultaneous’ (Tibetan cig-car) is a term to indicate the

immediate nature of Dzogchen, so that the inseparability of the three aspects

can be seen at a glance. The triangle shows the coincidence of time and the

Timeless, in a visible form. On this showing the simultaneous in visible form,

see also Rolf Stein’s article in Sudden and Gradual (Peter Gregory, ed.,

University

of Hawaii Press, Honolulu,

1987). Herein, on p. 55, he quotes a passage pointing to the contrast between ‘plastic

arts’ as being instantaneous, ‘wherein everything is available to be seen at

once’, and literature and music, ‘which imply a succession of events’.

4. The monk Daosheng (Tao-sheng, 360-434) is credited as having been the

first to emphasize this point of immediate availability of Buddha-nature for everyone.

See Whalen Lai, ‘Tao-sheng’s Theory of Sudden Enlightenment Re-examined’, in Sudden

and Gradual (Peter Gregory, ed., University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1987); p. 169-200.

5. In the words of Tulku Urgyen: “Buddha-mind is the unity of being

empty and cognizant, utterly without fixation.” As It Is,

Vol. II; p. 189.

6. This pill is explained and depicted in ‘I’ is a Door (Zen

Publications, Mumbai, 2017); p. 54-59.

7. Tulku Urgyen, As It Is, Vol. II; p. 47 and 196-197.

8. Tulku Urgyen, As It Is, Vol. I; p. 146. See also p. 202; and in

Vol. II p. 47 and 168.

.jpg)